Last Republic

All eyes were on the Fed and ECB last week, with both central banks increasing interest rates by 25 basis points as expected. But their future paths are diverging, with the Fed hinting of a possible halt to rate hikes while the ECB said it’s in no mood to pause. That comes even after data last week showed core inflation in the eurozone easing for the first time in six months in April. Markets didn’t react much to any of these events, and that’s captured by Wall Street’s brand-new “fear gauge” (the 1-Day Volatility Index), which shows investors are calmer ahead of major macroeconomic announcements. Elsewhere, the turmoil in the financial sector continued last week and claimed another victim. First Republic became the third bank to collapse in the past two months, wiping out shareholders in the second-biggest bank failure in American history. The episode triggered a major selloff in other regional bank stocks, with the worsening sentiment likely to accelerate the withdrawal of credit and ultimately dampen economic growth. Find out more in this week’s review.

Macro

Another meeting, another hike: the Fed raised its benchmark interest rate by a quarter of a percentage point on Wednesday, marking its tenth consecutive increase in just over a year. That took the federal funds rate to a target range of 5% to 5.25% – the highest level since 2007 and up from nearly zero at the start of last year. Fed Chair Jerome Powell hinted that Wednesday’s hike could be the central bank’s last one, but stopped short of declaring victory in the fight against high inflation, leaving the door open for more rate hikes should price gains remain more stubborn than expected. Powell also strongly pushed back against market expectations that the Fed will cut rates by the end of the year. The message suggests that the central bank will likely keep interest rates elevated to stub out inflation once and for all – even if the US economy struggles.

Across the pond, new data last week showed eurozone inflation ticked up slightly for the first time in six months in April. Consumer prices in the bloc were 7% higher last month from a year ago – a touch more than the 6.9% registered the previous month and above the flat reading forecast by economists. There was some good news though: core inflation, which strips out energy, food, and other highly volatile items to give a better idea of underlying price pressures, eased for the first time in 10 months. Core consumer prices rose 5.6% from a year ago in April – down from March’s record 5.7% advance and in line with economists’ estimates.

That deceleration in core inflation, along with new data last week that showed eurozone banks tightened their lending standards by the most since the region’s debt crisis in 2011, should back the case for the European Central Bank (ECB) to slow down its most aggressive rate-hiking campaign in history.

In fact, the central bank did just that last week, delivering its smallest interest-rate increase yet in its current battle with persistently high inflation. As expected, the ECB raised the deposit rate by a quarter of a percentage point to 3.25%, leaving it at its highest level since 2008. The move was the central bank’s seventh consecutive rate hike since mid-2022, and it signaled that there’s more still to come after warning that significant upside risks to the inflation outlook remain. Traders are currently betting that the deposit rate will peak at 3.70% by September.

Finally, it’s interesting to note that markets didn’t make any significant moves in response to the interest rate decisions or inflation report last week. See, while such announcements have a tendency of making investors very nervous, Wall Street’s brand-new “fear gauge” – the 1-Day Volatility Index, or “VIX1D” – shows diminishing anxiety over macroeconomic events of late.

Launched last month, the VIX1D measures the S&P 500’s expected volatility over the next trading day as a way of gauging short-term fear. Its calculations are based on options contracts on the S&P 500 with maturities of less than 24 hours (a.k.a. “zero days to expiration” options), which now make up about half of the S&P 500’s options trading volume. Investors tend to pile into these short-term options when major economic data are on deck, looking to make quick profits or hedge positions around events that in the past year have swung markets in big and unpredictable ways.

But investors’ fears around these big macro events have been fading, demonstrated by the VIX1D’s performance over the past year. You can see in the graph below that the fear gauge regularly spiked a day before either the release of an inflation report or the Fed’s interest rate announcement, but those jumps have become less pronounced this year. For example, on December 12, right before the newest US inflation data was released, the VIX1D surged to 47. By contrast, on the day before the latest inflation report on April 11, it closed near 19.

What’s behind the downtrend? It’s hard to say for sure, but with inflation softening for nine straight months and the Fed nearing the end of its rate-hiking cycle, the macro picture is less unpredictable and scary today than it was last year. Put differently, with inflation and rate hikes largely in the rear-view mirror, investors are perhaps shifting their focus to more traditional drivers of the stock market, like corporate earnings and valuation levels.

Stocks

Another month, another bank goes under. This victim this time is First Republic, which was shut down early last week by the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC), wiping out shareholders in the second-biggest bank failure in American history. First Republic was on the verge of collapse for almost two months as deposits dwindled and its business model of providing cheap mortgages to wealthy customers was pressured by rising interest rates. Those higher rates also pushed up the bank’s funding costs as well as led to huge paper losses on its portfolio of bonds and other long-term assets.

The bank, which is bigger than Silicon Valley Bank (SVB), becomes the third lender to be shut down by the FDIC in less than two months. There’s one beneficiary from the turmoil though: JPMorgan, which won the bidding to acquire First Republic’s assets, including about $173 billion of loans and $30 billion of securities, as well as $92 billion in deposits. The transaction is expected to generate more than $500 million of incremental net income a year, the company estimated. Under normal circumstances, JPMorgan’s size and existing share of the US deposit base would prevent it from expanding its deposits further via an acquisition. But these are far from normal times, and regulators were forced to make an exception.

JPMorgan's acquisition essentially acted as a bailout for First Republic's customers, including depositors. But the rescue deal failed to prevent a sell-off in regional bank shares, with investors growing more concerned about the stability of other mid-sized banks similar to First Republic and SVB. Case in point: the KBW Index of regional bank stocks slumped almost 10% last week – its biggest drop since SVB’s collapse back in March.

First Republic’s failure will most probably accelerate the withdrawal of credit, which is the lifeblood of the economy. See, tightening credit standards cause consumer spending and business investment to plunge, which derails economic growth. And the lending environment was already deteriorating even before last quarter’s turmoil in the banking sector. The latest episode of stress, then, will only intensify things by worsening credit conditions as banks tighten their lending standards in a bid to strengthen their balance sheets. The ensuing credit crunch, then, will only increase the odds of a recession…

This week

- Monday: Eurozone Sentix Economic Index (May), China loan growth (April). Earnings: Palantir Technologies, PayPal.

- Tuesday: China trade balance (April), Japan household spending (April). Earnings: Airbnb, Rivian Automotive.

- Wednesday: US inflation (April). Earnings: Disney.

- Thursday: China inflation (April), Bank of England interest rate decision.

- Friday: UK GDP (Q1).

General Disclaimer

This content is for informational purposes only and does not constitute financial advice or a recommendation to buy or sell. Investments carry risks, including the potential loss of capital. Past performance is not indicative of future results. Before making investment decisions, consider your financial objectives or consult a qualified financial advisor.

Did you find this insightful?

Nope

Sort of

Good

Investors Ditched US Stocks

%2FfPNTehGpuD8BdwDeEEbTF2.png&w=1200&q=100)

China’s Back In Deflation

%2FgRTFfWwPmcWyE8PFfywB82.png&w=1200&q=100)

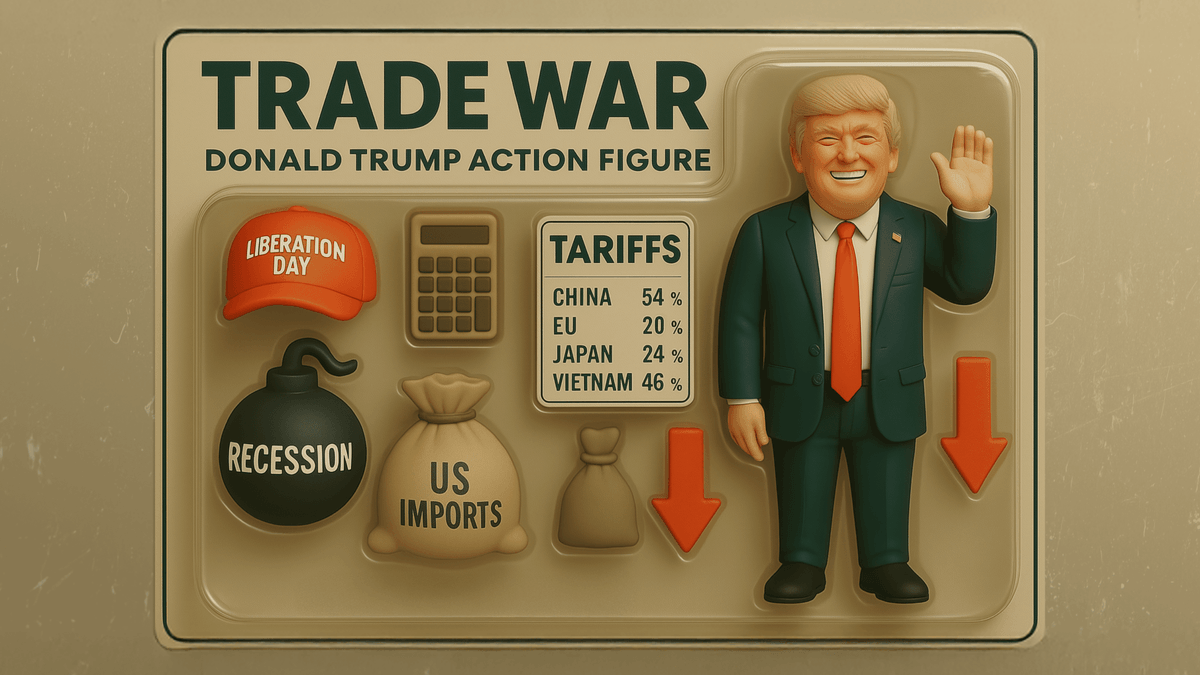

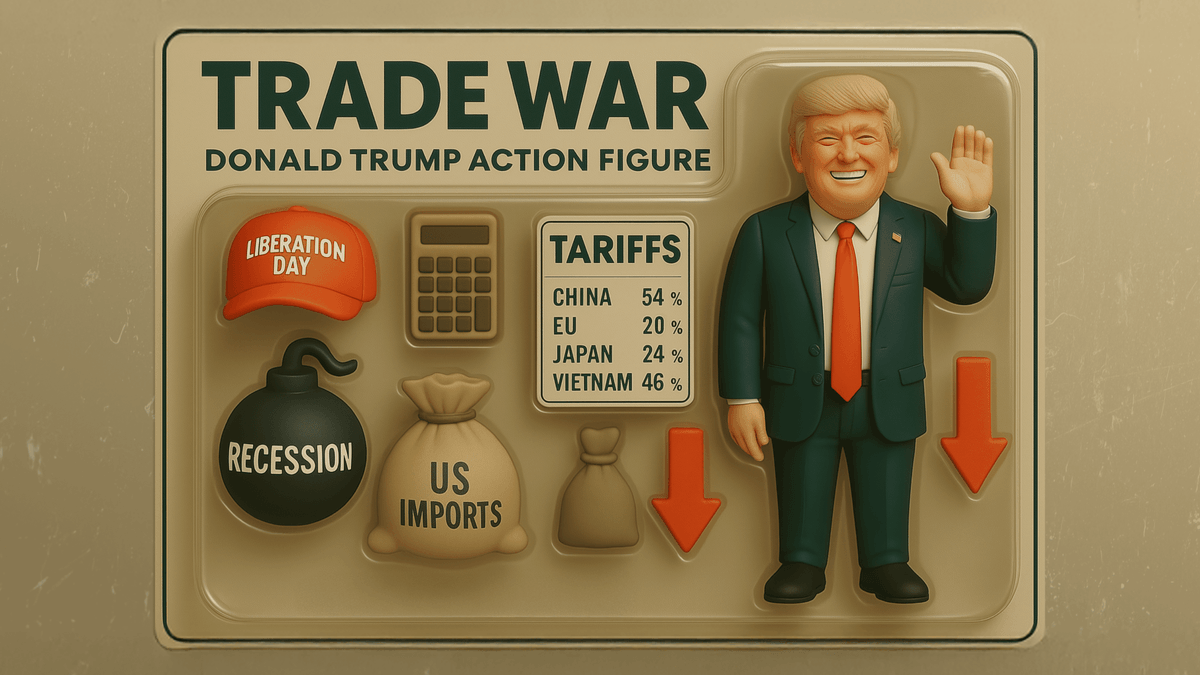

Trump Intensified The Trade War

Bitcoin Slumped

%2FAD2MfhoJXohkTgrZ5YjADV.png&w=1200&q=100)

Institutional Investors Are Bullish

Trump Tariffs Shake Markets

%2FjjqkumDfGjhNxroL253Hc4.png&w=1200&q=100)

Investors Are Tariff-ied

Cooling Inflation