An End Of An Era

Here are some of the biggest stories from last week:

- The Bank of Japan ended its long era of negative interest rates.

- Industrial production in China jumped at the start of the year.

- UK inflation cooled by more than expected in February.

- However, the Bank of England still opted to keep borrowing costs unchanged.

- The Fed also kept interest rates steady, while lifting its inflation and growth forecasts.

Dig deeper into these stories in this week’s review.

Japan

In a big move this week, the Bank of Japan delivered its first rate hike since 2007, scrapping the world’s last negative interest rate as well as a whole bunch of other unconventional tools designed to encourage spending over saving. Central bank members voted 7-2 in favor of raising the overnight interest rate from minus 0.1% to a range of 0%-0.1% (not a massive increase in the grand scheme of things). The decision comes as the BoJ becomes increasingly confident that its 2% inflation target is finally within sight, especially after workers at some of Japan’s biggest companies recently secured their biggest pay rise since 1991. That’s important for the BoJ, which sees strong wage growth as key to keeping inflation going after decades of economy-busting deflation.

The BoJ didn’t offer any guidance on future rate hikes, saying it’ll depend on incoming data, which left some traders in the dark. But it did scrap its yield curve control program, which consisted of not only keeping short-term rates low but also explicitly capping longer-term ones. However, it did pledge to continue buying long-term government bonds as needed. Finally, the bank said that it’ll discontinue purchases of exchange-traded funds and Japanese real estate investment trusts. The BoJ adopted the highly unusual measure in 2010, but with Japanese stocks at all-time highs, it’s fair to say that the equity market no longer needs support.

All in all, the bank’s indication that financial conditions will remain accommodative clearly showed that its first rate hike in 17 years isn’t the start of an aggressive monetary tightening cycle of the sort seen recently in the US and Europe. That prompted a slide in the yen and 10-year government bonds on Tuesday. The silver lining in the yen’s movement is that it may reassure some export companies and equity investors concerned that a strengthening of the currency would squeeze profits going forward.

China

The world’s second-biggest economy got some good news this week, with new data showing a strong jump in factory output and investment growth at the start of the year. Industrial production rose by 7% in January and February from the same period last year – the fastest rate of growth in almost two years and above the 5.2% increase forecast by economists. (Note that China’s statistical agency releases combined readings for the first two months of the year to smooth out volatility from the Lunar New Year holiday). Adding to the good news, growth in fixed-asset investment accelerated to 4.2% – the strongest pace since April. Retail sales, meanwhile, increased by 5.5%, which was roughly in line with projections.

The positive release was welcomed by investors, who are closely watching China’s economic data for any signs of improved momentum after a period marked by falling prices, fading consumer confidence, and a slumping real estate market. However, this week’s data provided little optimism on that last point, with the figures showing that the sector remains a major drag on the economy: property investment fell 9% and housing sales plunged 33% by value in the January-February period from a year ago, underscoring the deep structural issues within the sector.

UK

The Bank of England got some good news this week, with February’s inflation report showing the pace of price gains cooling by more than expected to its lowest level since 2021. Consumer prices rose by 3.4% last month from a year ago – less than the 3.5% forecast by the BoE and economists, and a marked declaration from January’s 4% pace, partly thanks to easing food prices. But even core inflation, which strips out volatile food and energy prices to give a better idea of underlying price pressures, cooled by more than expected, to 4.5%.

The better-than-expected figures prompted traders to increase bets that the central bank will start cutting its benchmark rate in the summer. But the BoE has insisted that it cannot relax monetary policy too prematurely given stubborn growth in services prices and wages. Case in point: services inflation, which officials see as a key gauge of domestic pricing pressures as external drivers of inflation such as elevated fuel prices fade, cooled by less than expected in February, to 6.1%.

Traders didn’t have to wait too long to get clues into the BoE’s thinking though, after it held rates at a 16-year high of 5.25% for the fifth consecutive meeting this week. Two central bank members who had previously called for higher interest rates dropped their stances, instead voting with the majority for unchanged rates. Governor Bailey struck an optimistic note, saying that while the bank is not yet at the point where it can cut interest rates, there are encouraging signs that inflation is coming down toward its 2% target. That prompted traders to further add to their bets for monetary easing this year, sending the pound and UK bond yields lower on Thursday.

US

As expected, Fed officials voted unanimously to leave the benchmark federal funds rate at 5.25% to 5.5% for a fifth straight meeting this week. Fed chair Powell echoed comments he and his colleagues have made in recent months, saying that officials want to see more evidence that inflation is coming down toward the bank’s 2% target before starting to cut rates. And while officials still expect to lower interest rates three times this year, more committee members now anticipate fewer cuts than that compared to before. For 2025, officials now see three reductions, down from four predicted in December.

The Fed said it now sees more upside risks to price pressures than before, and it increased its forecast for core inflation this year from 2.4% to 2.6%. On a positive note, it upgraded its 2024 economic growth forecast from 1.4% to 2.1%. Finally, Powell said it would be appropriate to slow the pace at which the central bank reduces its balance sheet of bond holdings fairly soon. The Fed has been winding down its holdings – a process known as quantitative tightening – since June 2022, and has been gradually increasing the combined amount of Treasury and mortgage bonds it allowed to run off, without being reinvested, to a total of $95 billion per month.

Next week

- Monday: US new home sales (February).

- Tuesday: US consumer confidence (March), US durable goods orders (February).

- Wednesday: Eurozone economic sentiment (March).

- Thursday: Eurozone M3 money supply (February), US pending home sales (February). Earnings: Walgreens Boots Alliance.

- Friday: Japan unemployment rate (February), US personal income and outlays (February), Japan industrial production and retail sales (February).

General Disclaimer

This content is for informational purposes only and does not constitute financial advice or a recommendation to buy or sell. Investments carry risks, including the potential loss of capital. Past performance is not indicative of future results. Before making investment decisions, consider your financial objectives or consult a qualified financial advisor.

Did you find this insightful?

Nope

Sort of

Good

Investors Ditched US Stocks

%2FfPNTehGpuD8BdwDeEEbTF2.png&w=1200&q=100)

China’s Back In Deflation

%2FgRTFfWwPmcWyE8PFfywB82.png&w=1200&q=100)

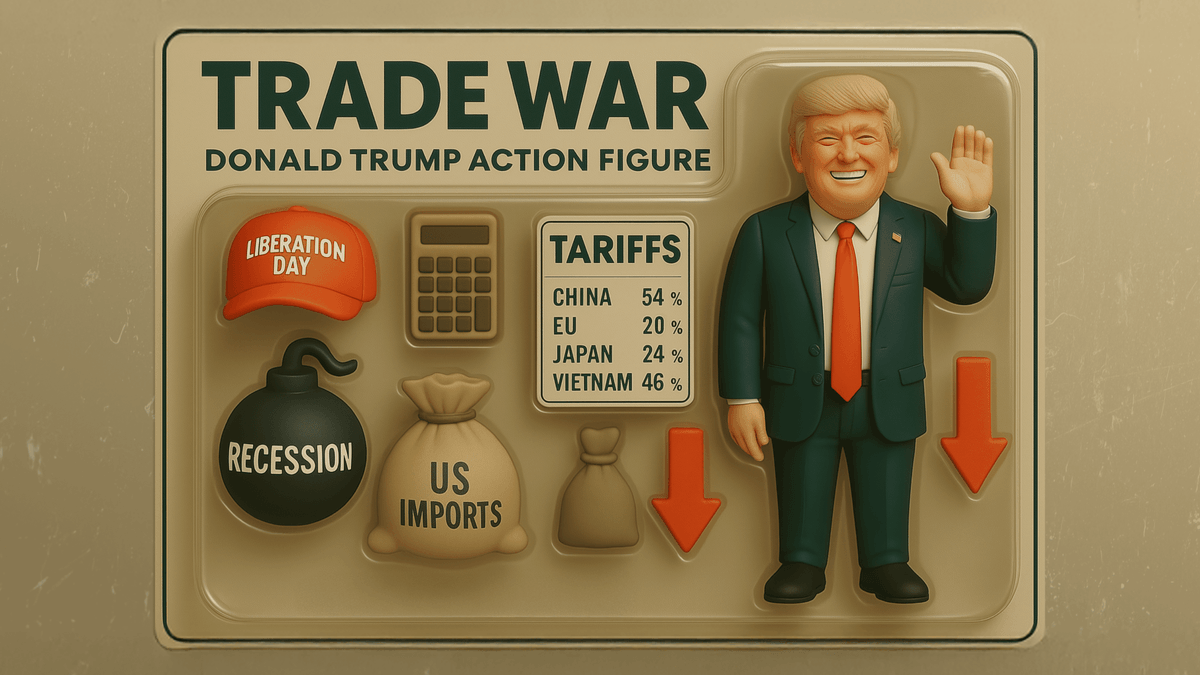

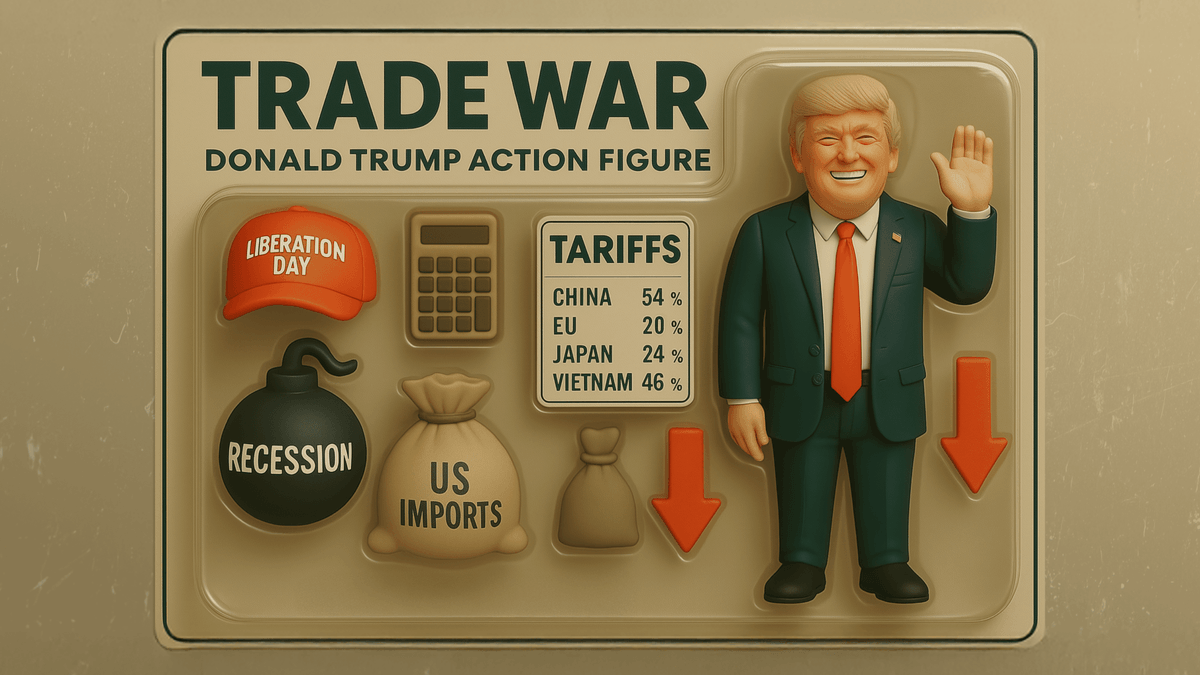

Trump Intensified The Trade War

Bitcoin Slumped

%2FAD2MfhoJXohkTgrZ5YjADV.png&w=1200&q=100)

Institutional Investors Are Bullish

Trump Tariffs Shake Markets

%2FjjqkumDfGjhNxroL253Hc4.png&w=1200&q=100)

Investors Are Tariff-ied

Cooling Inflation