Gold Shines at New Highs

Here are some of the biggest stories from last week:

- The IMF lowered its global growth forecast for next year.

- Chinese banks slashed their benchmark lending rates.

- The price of gold hit another record high.

- Treasuries have slumped since the Fed’s rate cut last month.

- US corporate bond spreads hit their lowest level in almost 20 years.

Dig deeper into these stories in this week’s review.

Global

The International Monetary Fund lowered its global growth forecast for next year and warned of rising geopolitical risks, from wars to trade protectionism. Global economic output will expand by 3.2% in 2025, or 0.1 percentage points slower than previously estimated, according to the IMF’s latest outlook released this week. It left its projection for this year unchanged at 3.2%. The US saw a 0.3 percentage point upgrade to its 2025 growth outlook on the back of strong consumption, while the eurozone’s forecast was slashed by 0.3 percentage points due to persistent weakness in Germany and Italy’s manufacturing sectors.

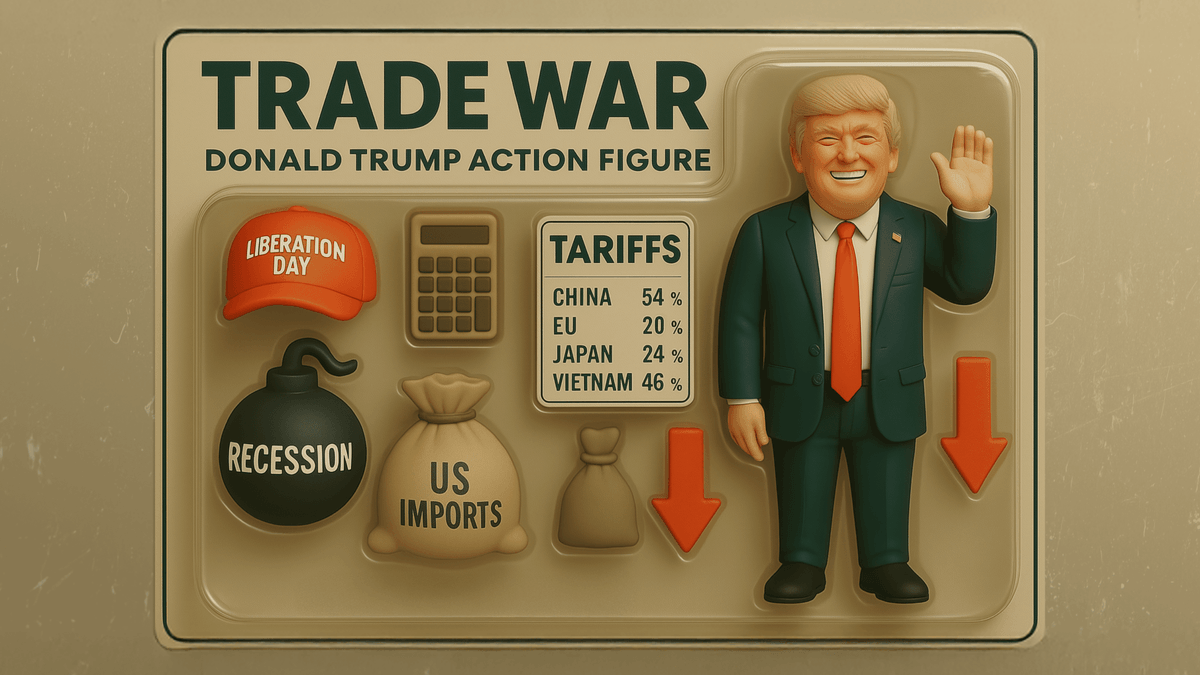

The IMF also issued a strong warning in its latest outlook, saying that if higher tariffs hit a large chunk of world trade by mid-2025, it would wipe 0.8% from economic output next year and 1.3% in 2026. The cautionary note may be indirectly aimed at Donald Trump, who has proposed imposing a 20% tariff on all US imports and a 60% tax on goods from China if reelected – actions that could prompt major trading partners to retaliate with their own tariffs on US goods.

China

China unveiled some of the biggest cuts to banks’ benchmark lending rates in years, as the government steps up efforts to boost the economy and hit its year-end target of about 5% growth. The People’s Bank of China said on Monday that the country’s one-year loan prime rate, which is set by a group of big Chinese banks and acts as a reference for consumer and business loans, would be reduced to 3.1% from 3.35% – the biggest reduction on record. Meanwhile, the five-year loan prime rate, which underpins mortgages, would be lowered to 3.6% from 3.85%.

The cuts come after the PBoC outlined steps last month to encourage households and companies to borrow more, including a reduction in the amount of money that banks must hold in reserve – a bid to nudge them to hand out more loans. Traders expect further easing in the coming months, including additional cuts to interest rates and the reserve requirement ratio. But whether that’ll be enough to alleviate China's longer-term deflationary pressures and entrenched real estate crisis remains to be seen. Skeptics argue that authorities have yet to introduce aggressive measures to boost consumer demand, which is seen as a crucial missing element for the economy. After all, making money cheaper to borrow won’t stimulate growth if Chinese consumers remain hesitant to spend…

Gold

Another week, another record: the price of gold hit an all-time high of $2,750 an ounce on Wednesday, taking its year-to-date gain to over 30%. There are several factors driving the rally. First, interest rates are falling in most parts of the world, reducing the opportunity cost of owning gold, which doesn’t generate any income. Second, central banks have been snapping up gold to diversify their reserves away from the dollar. In fact, during the first half of this year, central bank buying hit a record high of 483 tonnes, according to the World Gold Council. Third, gold is benefiting from increased safe-haven demand amid heightened economic and geopolitical risks, including slowing global growth, US election uncertainties, elevated China-Taiwan tensions, and ongoing conflicts in the Middle East and Ukraine. Case in point: gold ETFs have seen five consecutive months of global inflows from May to September.

Bonds

Here’s something odd: US government bonds have nosedived since the Fed’s first rate cut last month. In fact, the last time Treasuries sold off this much as the Fed started lowering interest rates was in 1995. More specifically, two-year yields have climbed 34 basis points since the US central bank reduced rates on September 18. Yields rose similarly in 1995, when the Fed managed to cool the economy without causing a recession. In prior rate-cutting cycles going back to 1989, two-year yields on average fell 15 basis points one month after the Fed started slashing rates.

At the heart of the selloff is a big shift in expectations about US monetary policy. Traders are reducing their bets on aggressive interest rate cuts since the world’s biggest economy remains strong, and Fed officials have been sounding a cautious tone about how quickly they will lower rates. Adding to the market's worries are rising oil prices and the potential for larger fiscal deficits after the upcoming US presidential election. As a result, volatility in Treasuries has surged to its highest level this year, according to the ICE BofA Move Index, which tracks expected changes in US yields based on options.

On the flip side, the US corporate bond market is having a great time as investors bet that the US economy is headed toward a "soft landing" – that dream scenario where the economy slows enough to tamp down inflation, but remains strong enough to avoid a recession. The yield gap between US corporate bonds and Treasuries shrunk to 0.83 percentage points this week – the lowest level in nearly 20 years. The spread between high-yield (or “junk”) bonds and government bonds, meanwhile, is at its lowest since mid-2007. That’s got some fund managers worried that the $11 trillion corporate bond market is too complacent about lingering economic risks or the potential for post-election turbulence. After all, with spreads so low, investors are getting very little protection against a potential rise in corporate defaults – especially considering that overall borrowing costs remain higher than the average in the decade and a half of near-zero interest rates that followed the financial crisis.

Next week

- Monday: Earnings: Ford.

- Tuesday: Japan unemployment (September), UK M4 money supply (September), US consumer confidence (October), US job openings and labor turnover survey (September). Earnings: Alphabet, AMD, McDonald’s, PayPal, Pfizer, Mondelez, Visa.

- Wednesday: Eurozone GDP (Q3), eurozone economic sentiment (October), US GDP (Q3). Earnings: Microsoft, Meta, Coinbase, AbbVie, Amgen, Caterpillar, Eli Lilly, Starbucks.

- Thursday: Japan industrial production and retail sales (September), Bank of Japan interest rate announcement, China PMIs (October), eurozone inflation (October), eurozone unemployment (September), US personal income and outlays (September). Earnings: Amazon, Intel, Apple, Mastercard, Merck & Co, Uber.

- Friday: US labor market report (October). Earnings: Chevron, Exxon Mobil.

General Disclaimer

This content is for informational purposes only and does not constitute financial advice or a recommendation to buy or sell. Investments carry risks, including the potential loss of capital. Past performance is not indicative of future results. Before making investment decisions, consider your financial objectives or consult a qualified financial advisor.

Did you find this insightful?

Nope

Sort of

Good

%2FfPNTehGpuD8BdwDeEEbTF2.png&w=1200&q=100)

%2FgRTFfWwPmcWyE8PFfywB82.png&w=1200&q=100)

%2FAD2MfhoJXohkTgrZ5YjADV.png&w=1200&q=100)

%2FjjqkumDfGjhNxroL253Hc4.png&w=1200&q=100)